What Tribal Students Teach Us About Equitable Education

- Dr. Atul Dhakne and Dr. Tejas Ahire

- Jul 17, 2025

- 4 min read

In the heart of India’s most neglected regions, students are proving that talent is universal even when opportunity is not.

In a nation where ‘merit’ is often celebrated as the sole determinant of success, the story of Ram Jimde from Gummalkonda in the remote backwater taluk of Sironcha in Maharashtra’s Gadchiroli offers a profound counter-narrative. Scoring an impressive 504 marks in NEET 2025, Ram is securing a prospective MBBS seat despite hailing from a village with no reliable mobile network or motorable roads. His father, a marginal farmer, could never have afforded the lakhs required for private coaching. Yet Ram’s achievement is not a miracle but the direct outcome of a carefully engineered ecosystem of support that enabled raw talent to flourish. His journey, alongside those of dozens of other students from our Lift For Upliftment (LFU) initiative, underscores a critical truth that academic excellence among India’s underprivileged is not merely a matter of innate ability but of unlocking potential through systemic, holistic scaffolding.

The landscape of educational inequity in India remains stark. While urban elites access premium coaching centers, students like Devdas Wachami (472 marks, NEET 2025) from the Naxal-affected region of Bhamragad, Gadchiroli, contend with infrastructural voids. For them, a library is a luxury and consistent electricity is a rarity. The pressure to abandon education for manual labour is immense. This year, of the 12.36 lakh students who qualified for NEET, only 67,234 were from the Scheduled Tribes category. For these students, clearing NEET is not just an academic milestone but a lifeline out of intergenerational poverty.

It is this disparity that LFU, since its inception in 2015 by medical students from B.J. Medical College, has sought to bridge. Our experience with over 450 students has shown that success hinges on a model built on three core pillars.

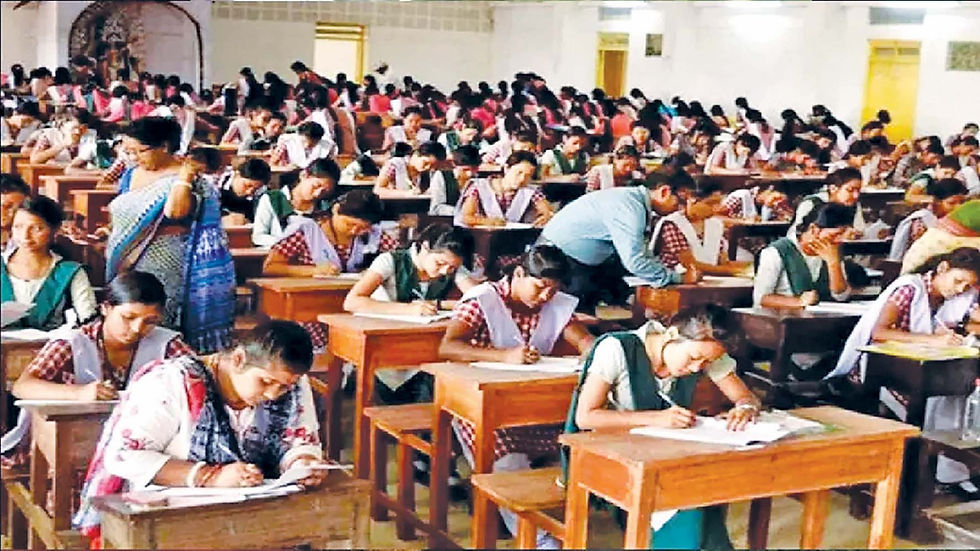

Firstly, contextual pedagogy. One-size-fits-all teaching fails rural and tribal students. Our ‘Ulgulaan’ residential branch, catering to students from Melghat and Gadchiroli, employs an anthropological approach. Recognizing that many tribal students are not fluent even in Marathi, let alone English, our volunteer-mentors use culturally resonant analogies. Biology principles are explained not through abstract concepts but through the observation they had in jungles. This approach, which respects their cultural context rather than dismissing it, is why 60% of our Ulgulaan batch students secure medical admissions every year.

Second, holistic nurturing. Merit cannot be cultivated in a vacuum. A student battling malnutrition or family distress cannot focus on complex scientific concepts. LFU’s residential program provides a controlled environment: nutritious meals, structured 10-hour study schedules, and a complete absence of mobile phones. All this is provided with care ethics approach. More importantly, it provides psychological safety. Our mentors are medical students, many from similar backgrounds, who understand the anxieties of being a first-generation learner. They are not just teachers but elder siblings who offer guidance, reassurance and a tangible example of what is possible.

Third, strategic intervention. Data shows that targeted support yields exponential returns. Krishna Gimbhal, Palghar, who scored 246 in his first attempt, improved his score by 171 marks after joining our repeater program inspite of increase in level of difficulty in NEET 2025. This year, approximately 31 of our students out of 76 are projected to secure MBBS admissions in government colleges. This success rate is a direct consequence of creating an environment where a student's only responsibility is to study—a privilege their urban counterparts take for granted.

The impact of this model extends far beyond individual triumphs. When students like Saniya Dhurve from Bhamragad, Gadchiroli aspiring to become doctors, they are committing to serving their own underserved communities, directly addressing India's rural healthcare deficit. Each medical degree in a family of marginal farmers creates a pathway for economic mobility, breaking cycles of debt and poverty. When young women from these backgrounds enter a prestigious profession, they dismantle entrenched gender and caste barriers.

This is not a task that can be left to NGOs alone. A systemic shift is imperative. State governments must replicate the residential support model in every tribal district, integrating it with the existing Ashram Shala system. Corporate India must move beyond sporadic donations towards long-term CSR partnerships that fund holistic educational ecosystems. Our collaboration with partners like Sahyadri Hospital and Narayana Health has been instrumental, but the scale of the problem requires a far broader coalition.

Ram, Krishna, Devdas and Saniya did not lack merit; they lacked opportunity. Their achievements demolish the convenient myth that talent alone is sufficient in a landscape skewed by privilege. As India charts its course towards becoming a developed nation, we must recognize that a true meritocracy is not about ensuring equal competition, but about providing equitable preparation. When we invest in the nutrition, mentorship and culturally sensitive education of our most marginalized students, we are not just creating doctors; we are building the architects of a more inclusive and prosperous India. The question before us is not whether such students can excel, but whether we, as a society, are willing to invest in the systems that make their success possible.

(The authors are co-founders of Lift For Upliftment (LFU), a pioneer NGO in free coaching for NEET-UG. Views personal.)

Comments