From Panipat’s Ashes: Peshwa Madhavrao and the Phoenix-like rise of the Maratha Empire

- Shoumojit Banerjee

- Aug 24

- 5 min read

With scalpel-like precision, Dr. Uday S. Kulkarni revives the drama of one of Indian history’s greatest recoveries.

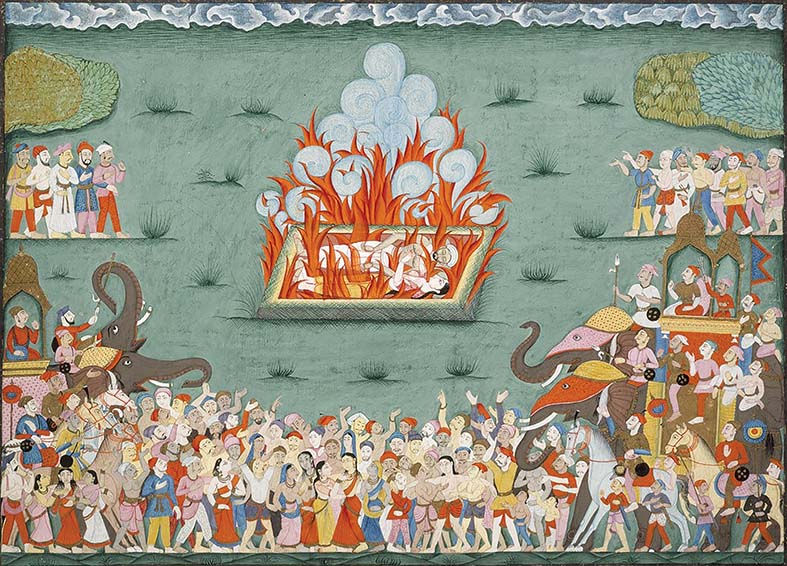

The Marathas’ recovery after the carnage of Panipat in January 1761 is one of the great comeback stories of Indian history. An early centrepiece of that comeback is the Battle of Rakshasbhuvan, that was fought this month and was among the most psychologically consequential of all Maratha victories.

On August 10, 1763, on the flooded banks of the Godavari near Rakshasbhuvan, the 18-year-old Peshwa Madhavrao came into his own and recovered Maratha self-belief shattered on the plains of Panipat when he defeated the Nizam of Hyderabad.

In his magisterial ‘The Mastery of Hindustan: triumphs and travails of Madhavrao Peshwa’ (2022), Dr. Uday S. Kulkarni tells the complex and little-understood story of how a young statesman steered the Maratha confederacy from the wreckage of Panipat towards a fragile but remarkable resurgence.

The Battle of Rakshasbhuvan, usually a footnote in histories of the Deccan and absent altogether from Delhi-centric narratives was in fact a hinge moment in 18th-century India and a contest that was as much about political legitimacy as it was about military supremacy.

It became the resurrection of a state that had staggered at the brink of annihilation, much like the Dutch Republic after the Spanish Fury of 1576 or the Habsburg Monarchy after its catastrophic defeat at White Mountain in 1620.

In Kulkarni’s expert hands, Rakshasbhuvan becomes a restoration of Maratha nerve and the re-establishment of deterrence along the Deccan hinge. Just as the Habsburg Monarchy recovered from near-collapse at the hands of the Ottomans, or the Dutch built a republic from the wreckage of Spanish repression, so too did the Marathas revive from the ashes of Panipat.

Like a young William Pitt steering Britain through the Seven Years’ War, Kulkarni’s Madhavrao grasped that states survive not by the glory of one battle but by the patience of many ledgers.

For anyone who cares about how states survive shocks, and how leaders craft authority from defeat, ‘The Mastery of Hindustan’ is an exemplar of the historian’s craft that is compulsively readable at the same time.

The shadow of Panipat hangs heavy over the narrative. In 1761 the Maratha confederacy was the pre-eminent power of the subcontinent, stretching from the Sutlej in Punjab to the fringes of Tamil country. Its defeat at Panipat at the hands of Ahmed Shah Durrani, however, shattered that dominance. Confidence in leadership eroded as a result while ominously, fissures within the Maratha polity widened.

It was a catastrophe comparable to the opening disasters for the Protestant cause in the Thirty Years’ War (1618-48) when Swedish, Bohemian and Dutch hopes seemed destined for eclipse under Habsburg steel.

What marks Kulkarni’s histories is the sheer depth of his immersion in the period. He writes like a surgeon-historian - with a steady hand, a keen eye and prose free of ostentation as he effortlessly decodes the tangled skein of 18th century Indian politics through its turbulent course in the Deccan, Bengal and the north.

Through letters, ledger entries, Persian akhbarats, Marathi bakhars and observations from British residencies,’ Kulkarni tracks armies and intrigues across half a continent with the patience of a cartographer.

His incredible research binds the written record to the lived landscape of the period, recalling the texture of great works like Sir Charles Oman’s The Peninsular War - attentive to the mud of the battlefield and the fog of decision, but never drowning the reader in minutiae.

The Maratha Confederacy was not a coherent empire but a loose federation of powerful families - the Holkars, the Scindias, the Gaekwads, the Bhonsales - each jealous of its prerogatives. Like the Holy Roman Empire, it was an unwieldy assemblage where centripetal forces constantly threatened cohesion. As Kulkarni shows, the fact that this polity held together in the 1760s and 1770s owed much to Madhavrao’s capacity to command and his immense courage.

That Madhavrao was obliged to govern with his uncle - the terminally erratic Raghunathrao - gives the narrative added tension. The other theatre in which Kulkarni excels is Mysore and the tangled intricacies of the ‘Deep South.’ Hyder Ali, that self-made general of cavalry and statecraft, had built a machine that ate revenue and territory with equal appetite. Between late 1764 and 1767, Madhavrao marched south repeatedly, humbling Hyder.

Dr. Kulkarni demonstrates that Madhavrao’s true distinction lay in suturing a fractured polity and restoring credibility to Maratha arms at a moment when their prestige was in tatters. It was a daunting feat reminiscent of similar statesmen-surgeons of Europe (albeit in different epochs and vastly different circumstances), like Richelieu who re-knit a France torn by sectarian strife or William of Orange, who held together a fragile Dutch Republic against overwhelming odds.

By marshalling letters, diaries and orders, Kulkarni allows his dramatis personae - adventurers, administrators, generals, courtiers - to speak for themselves. In doing so, he subtly rebuts a lazy assumption common in narratives leaning heavily on Company records that 18th-century Indian polities were nothing more than ‘military-fiscal states,’ surviving by the sword until Europeans supposedly taught them the pen.

Madhavrao’s centralising energies were inseparable from the politics of personality. When tuberculosis carried Madhavrao off at 27 in 1772, the polity shuddered.

Kulkarni’s definitive study makes clear that had he lived longer, the Marathas might have consolidated their mastery of India before the English East India Company rose to dominance. Madhavrao’s premature death - like that of Prince Henry Frederick of Wales (who died at 18 in 1612) whose early death dashed hopes of strong Stuart leadership and altered the fate of England - left a vacuum that others struggled to fill.

Dr. Kulkarni’s book is a joy to behold. Unlike most Indian works of history today, ‘The Mastery of Hindustan’ bears the unmistakable stamp of an author who has not only written but conceptualised and designed his project down to its smallest detail (as he has with all his works). Kulkarni has trekked every single fortress and battlefields he describes - Miraj, Channarayana Durga, Patthargarh - walking in the footsteps of armies who marched there two and a half centuries ago. He has collected rare images, hunted down unpublished documents (the casualty roll from the Battle of Moti Talao) and excavated forgotten bakhars with the care of an archivist and the imagination of a storyteller.

In this sense, he distinctly belongs to an older lineage of Indian historians like Jadunath Sarkar and Govind Sakharam Sardesai, who undertook arduous journeys in pursuit of their craft.

Extensive fieldwork as a habit has all but disappeared from Indian historical writing in the last several decades given the dominance of armchair Marxist historians. Yet in the West, the tradition forms a fundamental part of historical writing – be it the popular works of Peter Hopkirk, or that of brilliantly accessible classicists like Mary Beard, or Andrew Roberts, who traversed every site while researching his biography of Napoleon.

Likewise, for Dr. Kulkarni, who has almost single-handedly revitalised Maratha historiography of the Peshwa era for a new generation, history lives in the landscapes he describes, in the cracks of old ramparts and in the brittle pages of overlooked reports he has marshalled with such assiduity. It is this tactile engagement with his subject that makes his work not merely a chronicle of events but a reconstruction of a lost world.

His magnificent account reminds us that for a brief span, under a young Peshwa, India’s destiny might have been shaped not in London but in Pune.

Comments