Rewriting or Restoring? NCERT and the Myth of Secular Historiography

- Shoumojit Banerjee

- Jul 21

- 5 min read

Inconvenient Truths – the NCERT Textbook Row

India’s schoolbooks are finally lifting the veil on a past too long buried in euphemism and ideological amnesia. Our four-part series examines the roots of India’s textbook wars and the historiographical battles that have resulted in this distortion.

Part – 1

Far from communal provocation, the recent NCERT revisions reflect a belated academic honesty in acknowledging uncomfortable truths of India’s past.

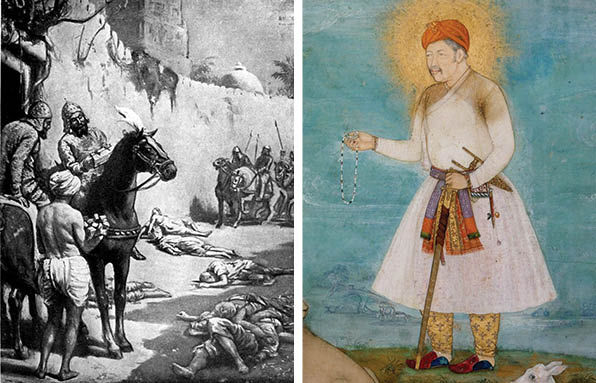

When the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) recently revised its Class 8 Social Science textbook to include a more candid reckoning with India’s medieval past by mentioning the dark deeds of the rulers of the Delhi Sultanate and the temple destructions of the first Mughal - Babur; the massacres ordered by Akbar the Great and the fanatical zeal of Aurangzeb, a predictable row ensued.

Critics from India’s entrenched academic elite (as well as a number of Western ones) and the so-called left-‘secular’ ecosystem decried the move as yet another attempt by the ruling BJP led by Narendra Modi to stoke the fumes of communalism and assert ‘Hindu supremacy’ by allegedly promoting an Islamophobic agenda.

The NCERT’s move was anything but incendiary. It came with a clearly articulated rationale titled ‘A Note on Some Darker Periods in History’ and included a cautionary disclaimer stating that “no one should be held responsible today for events of the past.” Far from stoking communal tension, these revisions - which have long been scrupulously documented by colonial-era and ‘nationalist’ historians (before the Marxists held sway) - sought to present history with honesty and context.

In fact, the NCERT’s move is a modest but long-overdue step in correcting decades-long intellectual dishonesty. For more than half a century, India’s schoolchildren have been subjected to a grotesque distortion of the country’s history in which foreign conquerors were whitewashed as cultural reformers, Islamic imperialism was repackaged as ‘composite culture’ and Hindu resistance was treated with embarrassment or omitted altogether.

This was no accident, but the outcome of a Nehruvian sophistry that held historical truth subordinate to the political necessity of preserving Hindu-Muslim amity in the wake of Partition’s horrors. In this telling, the trauma of medieval invasions had to be buried, lest it upset the fragile post-colonial consensus. The result, sanitized primarily through a Marxists lens, was that a generation taught to view India’s civilisational self-defence as chauvinism, and its conquerors as misunderstood unifiers.

To take a specific instance, in 1982, the NCERT (then under the long shadow of Congress rule), issued a set of Orwellian guidelines to historians preparing school textbooks.

“Over-glorification of the country’s past is forbidden,” the guidelines proclaimed. While it did caution against the glorification of Aurangzeb, it said in the same vein that “the Gupta Age can no longer be referred to as the golden period of Hinduism.”

No justification was offered. In order to achieve a lazy balance of ‘moral equivalence’ between the pre-Islamic and Islamic period, the 1982 guidelines simply decreed that an age during which Indian science, art, mathematics, literature and political unity reached heights unsurpassed even today must be stripped of its rightful appellation Pride, it seemed, was dangerous when it came to discussing or denoting any ‘golden age’ of Hindu civilisation.

The absurdity of this prescription becomes evident in comparative context. The Chinese celebrate the Ming dynasty. In the West, the wisdom of the Greeks and the splendour of the Romans is still celebrated (even while Roman barbarities are considered alongside) in form of figures ranging from Homer to Pericles, Anaximander to Aristotle and Cicero to Tacitus. The Arabs eulogise the Abbasids. The English revere the Elizabethan and Victorian ages, and the French glorify the Revolution, and, even with all their postmodern icons with their Derridean gobbledygook, still revere Joan of Arc and yes - Napoleon Bonaparte.

Why then, must Hindus alone be shamed out of pride in the Mauryan or Gupta periods?

The answer lies in the moral schizophrenia of India’s post-independence intellectuals who were desperate to forge national unity, yet unwilling to acknowledge historical grievance even when empirical evidence stared them in the face.

The 1982 guidelines’ most egregious distortion concerned medieval India. Muslim rulers, the document insisted, must not be referred to as foreigners except for those “early invaders who did not settle here.”

Consider the facts of this bizarre categorisation. The Arab conquest of Sindh in 712 CE led to permanent settlements in the region. The Turks, under Sabuktigin and Mahmud of Ghazni, had by the early 11th century not only settled in present-day Afghanistan and Punjab but established enduring political structures. Mahmud’s descendants ruled from Lahore for generations.

Muhammad Ghuri, whose invasions in the late 12th century led to defeat of Prithviraj Chaihan and the fall of Ajmer and later, Kanauj, never ‘returned’ anywhere. His lieutenants, like Qutb-ud-din Aibak, remained in India, laying the foundation of the Delhi Sultanate in 1210 CE.

But if permanence is the litmus test for nativity, then even the early Arabs qualify. If conquest is the test for imperialism, then most of these rulers fail it. But the 1982 guidelines wanted it both ways: to exculpate the Delhi Sultanate with its Mameluks, Turkish and Afghan Sultans and the Mughals by recasting them as ‘benevolent insiders,’ while condemning the British as out-and-out colonizing looters because they had a ‘homeland’ to return to.

This form of historical gymnastics was the outcome of an ideological consensus shaped by Nehruvian secularism and enforced by Marxist historians, many of whom were rewarded with sinecures at the Indian Council of Historical Research (ICHR) and NCERT itself. Their aim was not historical truth but apparently, national therapy for the Muslim populace who were recast as heirs to the Mughals and instructed to take pride in alleged ‘syncretic legacy’ of Indo-Islamic rule. Thus, any mention of Islamic iconoclasm, forced conversions, slavery or the destruction of temples was strictly verboten for fear of ‘offending’ minority sensibilities.

The historical record, if one dares to consult it, is unambiguous. The chroniclers of the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughals were certainly not bashful: Ziauddin Barani, Hasan Nizami and Amir Khusrau wrote in vivid detail and sometimes, unrestrained glee dripping with bigotry of the mass executions, enslavement of women and children, forced conversions, and temple demolitions of the Hindu ‘kaffirs’ as triumphs of faith.

Just read Nizami’s ‘Tajul-Ma’asir’ or Khusrau’s ‘Khazain-ul-Futooh’ (a vivid chronicle of Ala-ud-din Khilji’s reign) or better still ‘The Mulfuzat Timury’ (Timur’s autobiographical memoirs) and Aurangzeb’s own court records like the ‘Maasir-i-Alamgiri’ which boasts of destroying thousands of Hindu temples.

Even better, invest in the monumental eight-volume ‘The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians’ (1866-77) by H.M. Elliott and John Dowson if it is empirical evidence that one seeks. It is a sobering archive of Persian chroniclers narrating, often with chilling pride, the conquests, massacres, enslavement and desecration that accompanied Islamic invasions.

Predictably, cavillers tired of this litany of violence say “we need multiple perspectives.” Of course we do. There must be an emphasis on studies of trade and commerce, irrigation and agrarian systems and Indo-Persian cultural exchanges. But ‘multiple perspectives’ cannot become a euphemism for distortion, selective amnesia or whitewashing of atrocities. You cannot build an honest historiography on wilful erasure.

A truly mature civilisational discourse must distinguish between nuance and negation. To study the fluidity of Sufi thought or the emergence of Indo-Islamic architecture does not require denying the dark deeds of Mahmud of Ghazni or Shah Jahan or Aurangzeb. A textbook that speaks of trade with Central Asia cannot not speak of Timur’s sack of Delhi, where tens of thousands of innocent Hindus and Muslims were slaughtered in cold blood.

All this apart, the very notion that a 21st-century Muslim professional, entrepreneur or artist must be ‘protected’ from (well-documented) facts about dark deeds of their co-religionists may have done 800 years ago is itself bizarre in the extreme, as is the notion of holding any Hindu responsible for the misdeeds of his or her forebears.

But the quest for ‘balanced history’ cannot come at the cost of suppressing foundational truths. For history to truly educate, it must first illuminate. The ‘revised’ NCERT textbook does not incite hate; it simply restores complexity, and ends a long charade of wilful amnesia.

Comments