Bollywood’s Annus Mirabilis

- Shoma A. Chatterji

- Jan 17

- 3 min read

Author Pratik Majumdar’s latest book argues that 1975 transformed Bollywood in ways memory has flattened.

Sadly, whenever we go into a flashback to 1975, all discussions boil down to Sholay, a milestone in the history of Indian cinema and perhaps also, across world cinema. “Sadly” because, few are aware that 1975 can be defined as the Golden Year of Bollywood cinema. Did you know that not less than 80 full-length feature films were released across theatres in India and some of them were big hits too? Few might have kept a count but film buff and author Pratik Majumdar reminds us of these milestones that mark the history of Bollywood.

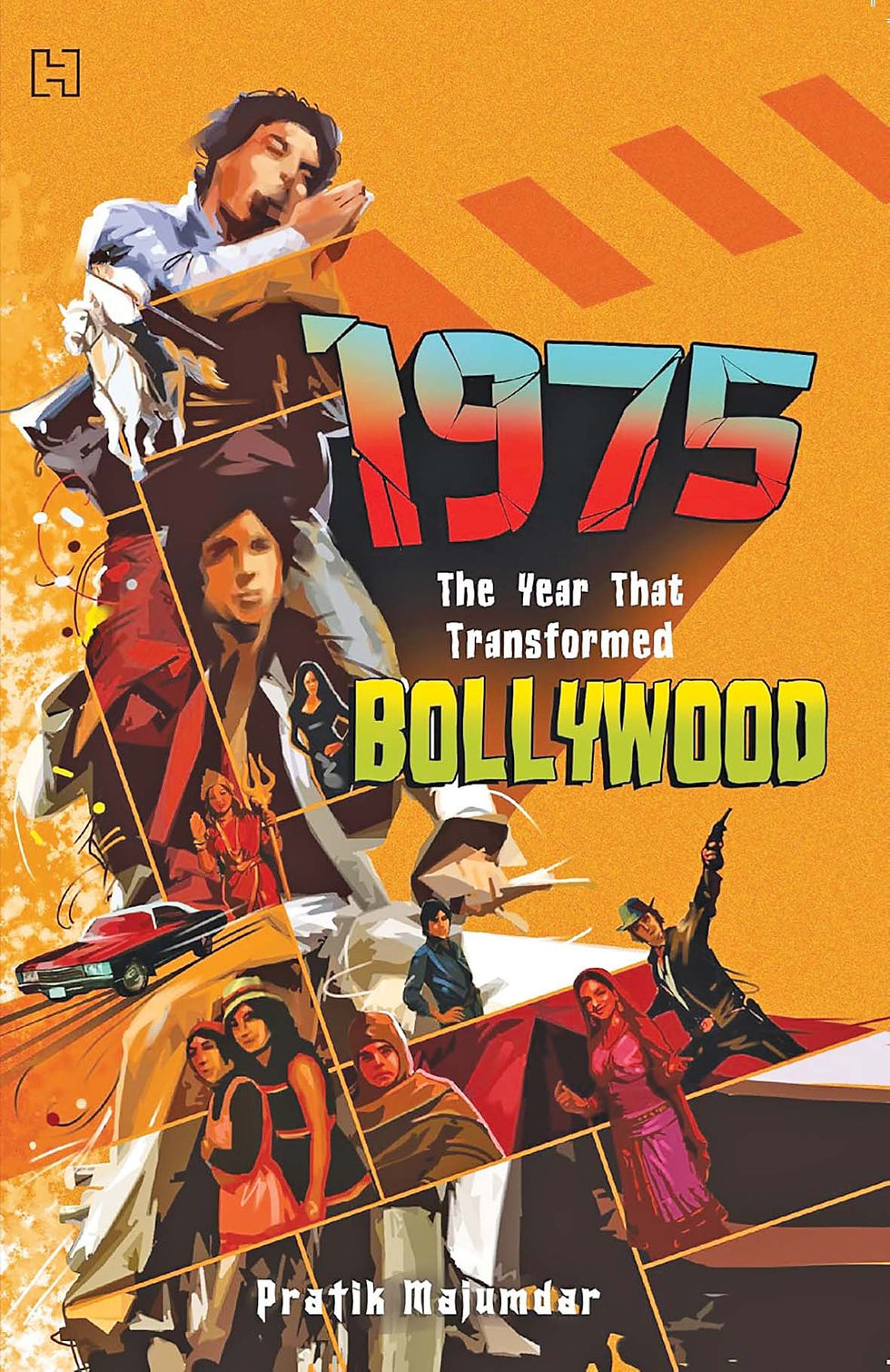

Watching films has been Majumdar’s passion and he has been actively pursuing it from the time he was ten or eleven. A couple of years ago, Pratik decided to record his passion for cinema, especially Bollywood. The result is in the 197-page extensively researched book published by Hatchette-India last year. The book is titled 1975 – The Year That Transformed Bollywood with a colourful collage for a cover with an image from Sholay dominating the cover.

The most outstanding quality of Pratik’s selection of around 30 feature films in the study is the underlining of the fact that Sholay might have been the best but this in no way signifies that other good films that hit the box office in a big way or landed on the wayside had not released in theatres.

The most important function of Bollywood – its cinema and the people who inhabit the film industry is its ability to act as an interface between traditions of Indian society and disturbing modern or Western intrusions into it. The Hindi film is a means of giving cultural meaning to Western structures superimposed on society, demystifying some of the culturally unacceptable modern structures now in vogue and ritually neutralizing elements of the modern world that must be accepted for sheer survival. Are Western intrusions into the Hindi mainstream film ethos really disturbing?

Not really, because the emphasis is not on the inner struggle between modernity and tradition. Nor is it on any deep ambivalence towards the West. The function of the Hindi film according to Shyam Benegal is to externalize an inner psychological conflict and handle the inner passion generated by social and political processes as problems created by events and persons outside. These events and persons are both ideal types and representatives of different aspects of a fragmented self. These fragments are separately controlled.

Bollywood seeks to sustain this control by sharpening the focuses of these differences - the hero and the anti-hero, the heroine and the anti-heroine, the large-hearted father-in-law and the middle-aged don. Hindi cinema does this because integration of these separate fragments into a unified whole would highlight the gray elements of characterization that it does not wish to adhere to. The cinematic influences of a foreign culture cannot uproot the cultural roots of a nation dotted with a largely illiterate mass population nurtured on a steady and generous diet of mythology, folklore, theatre, folk arts, music, all of which are reflected, represented, interpreted, distorted and questioned in and by popular cinema.

Pratik sheds light on films lesser-known than Sholay that were released the same year. Those films that were mainstream but had distinctive individual traits of the director are – Feroz Khan’s stylish Dharmatma, Shyam Benegal’s innocent filmization of Habib Tanvir’s famous play Charandas Chor, Rajshri’s super-duper hit Geet Gata Chal, Randhir Kapoor-directed Dharam Karam which is perhaps the first film in which the director directed his illustrious father Raj Kapoor, Brij Sadanah’s Chori Mera Kaam, three films of Gulzar, Shakti Samanta’s Amanush, Basu Chatterjee’s Chhoti Si Baat and many more.

There are five analytical essays also which sheds light on special areas of Bollywood cinema such as ‘The Impact of the 1975 Emergency on the Hindi film industry.’ Majumdar’s writing style is fluid, completely devoid of technical jargon and academic theorizing which enhances the book’s readability.

An outstanding feature is his dissection of Jai Santoshi Maa, which was released the same year. This film led to a kind of mass hysteria among Indian women throughout the country trapping most of them in a fiery fervour of rituals, fasting and prayers for 16 consecutive Fridays to seek her blessings through fulfillment of their vows. Interestingly, it is this film which created this Goddess which did not really exist before. Thanks to the film, the worship in temples dedicated entirely to Santoshi Maa sprung up right across India and women still pay obeisance to her.

This is a must-read book for everyone interested in cinema with special focus on Bollywood cinema.

(The author is a film scholar. Views personal.)

Comments