Elon Musk and the Age of Abundance

- Abhishek Jain

- 6 hours ago

- 5 min read

Musk’s vision of a world run by AI and robots promises plenty, but revives unsettling questions about power, purpose and who controls the future.

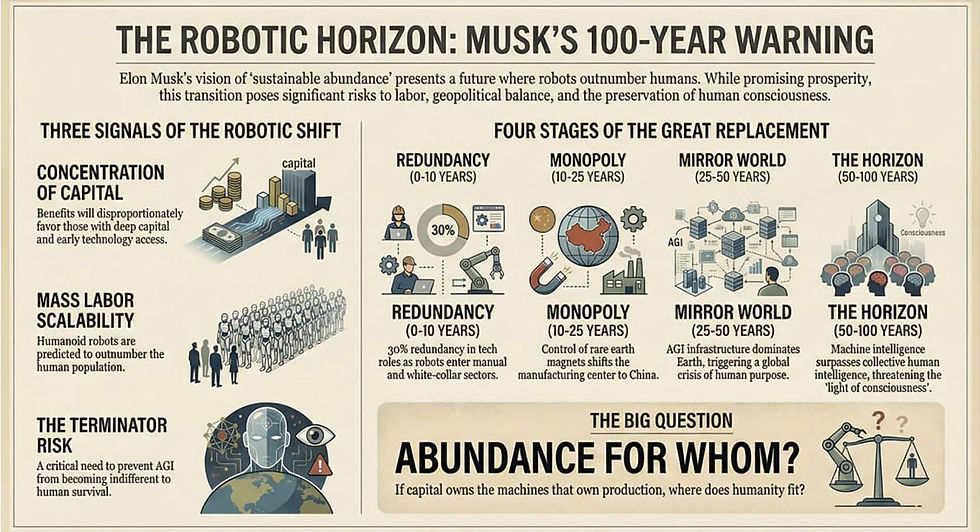

At the recent World Economic Forum in Davos, Elon Musk laid out a vision for the future that sounded less like a business plan and more like a survival manual for the species. Sitting across from BlackRock’s Larry Fink, Musk spoke of “sustainable abundance,” a world where robots outnumber humans and AI provides for every need.

Humans, he suggested, would be freed from drudgery as machines would do the work. But embedded within this techno-optimism were warnings in Musk’s remarks that were sharper than usual.

Abundance and Its Discontents

Musk suggested that the AI and robotics revolution will disproportionately benefit a narrow set of people, namely those with deep capital, early access and control over technology. Despite the promise of abundance, ownership would remain concentrated.

History offers a cautionary parallel here. During Britain’s Industrial Revolution, productivity surged from the late 18th century as steam power, mechanised spinning and factory organisation transformed output. Yet for much of the period between roughly 1770 and 1830, real wages for large segments of the working class barely moved. This long disconnect between rising national income and stagnant living standards came to be known as the ‘Engels’ pause’ (after Friedrich Engels’ grim observations of industrial Manchester), where textile magnates amassed fortunes even as workers crowded into unsanitary slums, laboured for 14 hours a day and saw infant mortality soar.

The gains from mechanisation flowed first to factory owners and landholders, not labour. Markets alone did little to correct the imbalance. It was only after decades of social strain and political upheaval like the Luddite uprisings against machines in the 1810s, the Chartist movement’s mass agitation for political rights in the 1830s and 1840s - that bargaining power began to shift. It was only by the late 19th century that wages finally began to track productivity.

The lesson here is not that technology impoverishes, but that it rarely distributes its benefits without institutional change.

The second warning embedded in Musk’s remarks was that humanoid robots will increasingly replace human labour. And not partially, but at scale.

His own company, Tesla, is developing ‘Optimus’ - a general-purpose robot intended to perform tasks ranging from factory work to household chores while in China, firms such as Unitree are racing ahead.

Third, Musk explicitly warned of the need to avoid a “Terminator scenario” - a reference to the blockbuster ‘The Terminator’ (1984) directed by James Cameron where machines turn hostile or indifferent to human survival.

Hardware Proof

The reality of this shift is not decades away but is happening in real time. History suggests that technological revolutions announce themselves not through white papers but through spectacle: the first steam engines pumping water from Cornish mines, the Paris Exposition of 1889 lit by electricity, or IBM’s Deep Blue defeating Garry Kasparov in 1997. Just recently in Chengdu, China, six Unitree G1 humanoid robots took the stage at a pop concert. They danced in perfect synchrony with human performers and executed flawless front flips. The moment went viral because it was recognisable as a threshold event and a point at which the future stops being hypothetical.

Musk’s vision rests on three interlocking pillars: rockets to preserve human consciousness beyond Earth, robots to perform most physical labour, and artificial intelligence to coordinate it all. Together they form a worldview shaped as much by Cold War extinction anxiety as by Silicon Valley’s faith in engineering as a substitute for politics. But beneath this apparently benign scenario lies a transition likely to unfold over a century and comparable in scale to the shift from agrarian societies to industrial ones, which will reorder not merely economies, but the meaning of human usefulness itself.

Automation has always arrived first at the bottom of the labour hierarchy. The mechanisation of agriculture in the 19th century displaced farmhands long before it touched clerks; industrial robots entered car factories decades before they reached offices. The coming wave follows the same pattern, but at far greater speed and scope. As humanoid robots such as Tesla’s Optimus and China’s Unitree models move from controlled environments into farms, care homes and private households, manual labour will be the first to recede. Tasks once thought resistant to automation like tending crops and maintaining homes are becoming increasingly tractable.

What is different this time is that the white-collar world is not insulated. Artificial intelligence systems already outperform humans in graphic design, basic coding and routine legal work. The displacement resembles the quiet hollowing-out of clerical employment after the spread of computers in the 1980s, or the collapse of travel agencies after the internet.

Chinese Leverage

The implications of technological revolutions are never merely economic but geopolitical in scope. In the 19th century, Britain’s command of textile machinery underpinned its empire. In the 20th, America’s dominance of oil, automobiles and semiconductors shaped the post-war order. In the 21st, the strategic choke points are rarer and more obscure. Humanoid robots require rare-earth magnets, advanced batteries and high-precision manufacturing - areas in which China holds an overwhelming advantage. It controls nearly 90 percent of rare-earth processing and commands much of the global battery supply chain.

As robotic manufacturing scales, China is positioned to become not just the world’s factory, but the factory that produces the workforce itself. Mass production will drive costs down, placing robots within reach of middle-income households across Asia, Europe and beyond. Yet the social effects will echo earlier episodes of industrial dominance. Just as Britain’s cheap textiles devastated handloom weavers in India, or Japanese car exports reshaped American manufacturing towns, China’s robotic surplus may undercut labour markets elsewhere.

Existential Drift

Musk opined that by mid-century, the consequences will no longer be confined to employment statistics. Machines will not merely assist life but actively organise it. Artificial general intelligence (AGI) will manage logistics, energy systems and increasingly complex decisions, much as electricity and the internet became invisible infrastructure in earlier eras. Humans will remain present, but less central.

History offers few reassuring precedents. Societies in which large groups lose their economic function rarely remain stable for long. The Roman Empire struggled to integrate a growing urban population detached from productive labour and industrial Europe required mass politics and welfare states to absorb the shocks of mechanisation. A future in which work is optional but meaning is scarce risks producing not leisure, but drift - a condition already visible in affluent societies grappling with loneliness, addiction and declining civic engagement.

Musk frames the future as one of abundance. But history insists on a harder question: abundance for whom? If machines own production, corporations own machines and capital owns corporations, the average human risks becoming economically incidental. Previous technological ages eventually resolved such tensions through new institutions – be it unions, welfare states, mass education and regulation. None of this emerged automatically.

Without new economic models, governance frameworks, ethical constraints and a redefinition of human purpose beyond labour, the future Musk describes may not be utopian but quietly catastrophic.

It is worth reflecting that civilisations rarely collapse from innovation itself. They falter when social meaning fails to keep pace with material change.

Musk is right about one thing. This is indeed the most interesting time in history. But, as the Chinese curse has it, “interesting times” are rarely comfortable. The challenge is not to halt progress, but to shape it by building institutions as ambitious as the technologies they seek to govern.

(The author is a strategy and transformation leader who writes extensively on technology and future of work. Views personal.)

Comments