Maharashtra’s Rankean Chronicler and the Final Word on Shivaji Maharaj

- Shoumojit Banerjee

- Sep 18, 2025

- 5 min read

In a lifetime devoted to relentless scholarship, Mehendale sifted legend from fact, giving the Maratha ruler the biography he truly deserved

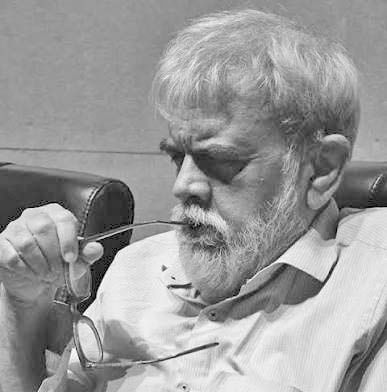

The prodigious Gajanan Bhaskar Mehendale, who passed away aged 77 in Pune, was a comprehensive debunker of the many myths associated with Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj and the historiography on the legendary 17th century Maratha warrior king.

A figure of Olympian erudition and quiet humility, Mehendale belonged to that now-extinct species of scholars whose lineage ran through luminaries of the late 19th and early 20th stalwarts like Sir Jadunath Sarkar, Vishwanath Kashinath Rajwade, Vasudev Vaman Khare, G.S. Sardesai – whose craft was defined by a stern fidelity to evidence and the conviction that history was a serious and rigorous discipline that could not be subjected to frivolous ideological sloganeering or faddish theorizing.

That Mehendale, in his 950-page tour de force Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj: His Life and Times (2011), could so effortlessly expose the flaws in the great Sarkar’s Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj and His Times (1919) - a biography that had long dominated the field of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj studies in English - stands as a testament to his scholarly authority and exacting method.

He tellingly began his monumental biography of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj with the famous quote from John Adams, made during the latter’s ‘Argument in Defense of the Soldiers in the Boston Massacre Trials’ in December 1770: “Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passion, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.”

Mehendale’s masterwork, the product of a staggering 30 years of dedicated research, stands as the most technically perfect biography of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, with its fascinating appendices and every controversy and misconception examined in forensic detail.

Born in 1947, the year of India’s independence, Mehendale grew up in an atmosphere where Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj was both folk memory and nationalist icon. He trained first as a student of defence studies at the University of Pune, and even worked as a war correspondent during the Bangladesh War of 1971 before turning fulltime to history research.

In his magnum opus, he admitted that like most Maharashtrian boys he had grown up revering Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Maharaj; what changed was the nature of his reverence. As he read widely in military history, he realized that Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj could be counted among the “great captains of the world” and that his legacy was not just that of a daring cavalryman but also of an astute administrator, a humane statesman and a builder of institutions.

That recognition could have led him down the road of hagiography. Instead, Mehendale became a myth-breaker. Like an ace detective, he forensically cherished myths that abound in the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj’s exploits and the great ruler’s milieu.

A person who absolutely shunned any manner of celebrity, Mehendale was at home in the libraries and archives of Pune and elsewhere in Maharashtra, spending the best part of his research life at institutes like the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhak Mandal (BISM) and the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute (BORI), immersing himself in Modi scripts, Persian chronicles, Portuguese records, neglected Marathi bakhars, digging up old letters and correspondence to understand and present as definitive a picture of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj and 17th century Maharashtra as was possible.

When it was finally published in English, Mehendale’s ‘Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj: His Life and Times’ became a running dialogue with earlier chroniclers, correcting, nuancing and sometimes outright dismissing their claims, especially in Sarkar’s biography of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj.

For instance, Mehendale debunked stories that the fort of Kondhana was renamed Sinhgad only after Tanaji Malusare’s death in its recapture, observing that a 1663 letter already called Kondhana as ‘Sinhgad,’ seven years before its recapture by Tanaji in 1670.

He further corrected notions of scholars that an awakening in Maharashtra owing to the work of saints had laid the groundwork for Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj’s coming. Likewise, he debunked the notion that Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj’s many marriages were all politically motivated, noting that even a lesser noble like Kanhoji Jedhe had five wives.

Mehendale further refuted the opinion of James Grant Duff and Sarkar that Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj was illiterate, pointing that in the absence of any hard evidence, such a claim on Grant Duff’s part (and echoed by others) carried with it a whiff of sensationalism.

Mehendale pointed out how Sarkar dismissed most Marathi documents as undated, unreliable or altered, while himself relying heavily on undated Persian collections. Sarkar, he argued, had failed to engage with Marathi sources in depth, and in doing so allowed myth carelessness to creep in what Mehendale termed a ‘half-baked’ biography of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. While Sarkar was a master of Persian sources and a formidable chronicler of Aurangzeb and the fall of the Mughal Empire, but to Mehendale’s mind, he had only dabbled in Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj.

Dr. Bal Krishna’s two-volume Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj the Great (1931), the other widely read English biography which made effective use sources, suffered the opposite problem. It was passionately nationalist, a work of uplift rather than of inquiry. Where Sarkar was sceptical, Bal Krishna was celebratory.

However, the biography which Mehendale gives of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj is sober without being bloodless, proud without being parochial. It was in his appendices, those dense but absorbing collections of letters, farmns, and cross-examinations, that one saw his craft at its clearest. Readers linger there not for narrative pleasure but for the thrill of evidence itself, which Mehendale sifted and arranged with lawyerly care.

While giving a talk on truths and half-truths in history, Mehendale took aim at the easy relativism that passes for historical wisdom. “Some people, who are perhaps too indolent to study Persian or the Modi script, keep saying history keeps changing,” Mehendale had remarked. “It is my belief that ninety per cent of history remains as it is. Ten per cent may change owing to new evidence,” he said, in a thinly-veiled rebuke to so-called ‘progressive’ or Marxist historians.

It was his firm view that the historians’ job is not to ‘guide’ society but only to tell from documents what happened. Mehendale’s fastidiousness in source criticism recalled Barthold Georg Niebuhr, who in the early nineteenth century revolutionized Roman history by discarding legend. His devotion to documentation echoed historians like Ranke and Guizot.

It is imperative that his other works in Marathi like ‘Islamachi Olakh’ and ‘Shivachatrapatinche Aramar’ (The Navy of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj) be translated in English and other vernacular languages to enable the country to know the full measure of Mehendale’s scholarly rigour.

In his biography of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, Mehendale joins a rare company of historians who have completely reshapes the very study of their subjects: Golo Mann with Wallenstein, David Chandler with Napoleon’s campaigns, Stephen Kotkin with Stalin or Ian Kershaw with Hitler.

Just as the masterworks of these historians rendered earlier accounts of their subjects provisional, Mehendale’s ‘Shivaji: His Life and Times’ made the works of Sarkar and others seem like a first draft.

It is hard to imagine any matching the comprehensiveness of Mehendale’s magnum opus. Its meticulous appendices, its demolition of errors large and small ensures that it will remain the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj biography to end all biographies – and the volume that every serious student must confront.

In this sense, Gajanan Bhaskar Mehendale accomplished something rare by writing a work so thorough and so definitive that it may never be superseded.

And that is the highest tribute one can pay a historian. He did what Leopold von Ranke demanded, what John Adams urged, what he himself practiced: he gave us the historical Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, not as a plaster saint or a polemical symbol but as he really was.

Comments