A Quiet Man in Noisy Times

- Abhijit Joshi

- Jul 4, 2025

- 4 min read

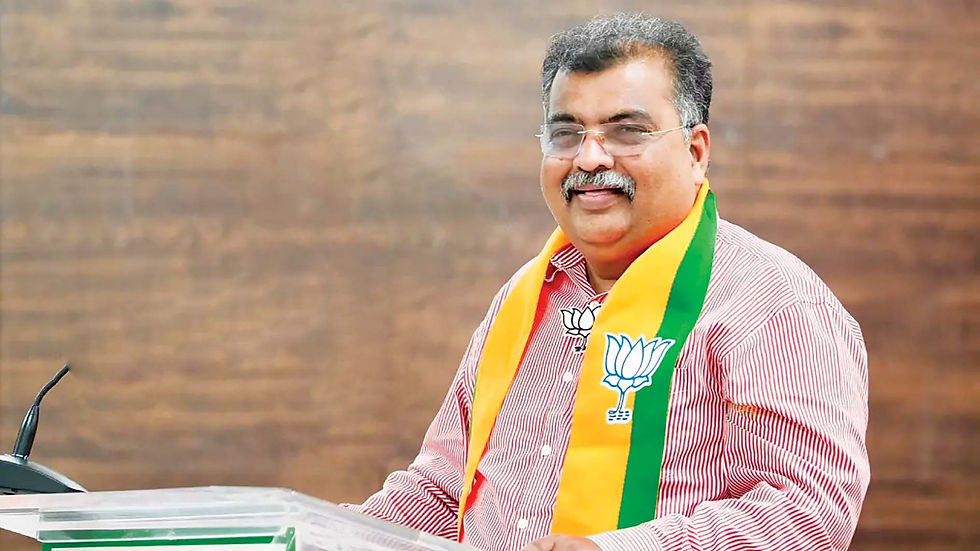

Can Ravindra Chavan’s low-key leadership rescue a disoriented BJP in Maharashtra ahead of crucial civic elections?

As readers sip their morning tea while reading this article, two thoughts may be brewing. First, why did Devendra Fadnavis, the Bharatiya Janata Party’s helmsman in Maharashtra, fail to contain the Hindi language controversy that stirred Marathi sentiments and sent tremors through the state’s politics?

Second, attention is now fixed on Ravindra Chavan, the newly appointed state BJP chief. Can he calm the waters, restore the morale of the party’s demoralised cadre, and chart a course toward revival? Looming behind these questions is a larger one: is Maharashtra, long a battleground of regional pride and national ambition, preparing to re-embrace the Thackeray brothers?

When Ravindra Chavan was appointed working president of the Maharashtra BJP on January 20th, 2025, many foresaw a rocky road ahead. Five months on, much of that unease persists. The state unit has failed to tackle key challenges or articulate a clear vision—either to its karyakartas or to the wider electorate.

The party leadership appears adrift. It lacks authority over the second-rung leadership and has grown distant from its grassroots base. The most striking example came on June 29th, when the state government was forced to withdraw two Government Resolutions mandating Hindi as a third compulsory language from Class I. The hasty move triggered a backlash that cut across party lines and inflamed Marathi pride.

Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis had to beat a retreat, scrapping the decision and appointing a committee to re-evaluate language policy under the NEP 2020 framework. The reversal has not only dented the BJP’s credibility in Maharashtra but has also raised uncomfortable questions at the national level about the party’s ideological coherence and muddled communication.

The BJP may have believed it had put the Hindi language row to rest. In truth, the Thackeray brothers deftly seized the moment, using the controversy to reconnect with Marathi-speaking voters. For a party that once branded itself one with a difference, the BJP has appeared surprisingly tone-deaf to the emotional and cultural undercurrents at play.

Its repeated overtures to Raj Thackeray, chief of the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena, have also puzzled observers. While dialogue has its place in politics, treating such engagements as masterstrokes of ‘Chanakya Niti’ risks backfiring, especially if not accompanied by clear messaging and grassroots follow-through. Meanwhile, any internal manoeuvres aimed at undermining allies such as Deputy Chief Minister Eknath Shinde may only deepen confusion within the BJP-led alliance.

Relentless attacks on Sharad Pawar, Uddhav Thackeray or Rahul Gandhi may offer red meat to loyalists, but they do little to address voter concerns. If anything, the BJP would do well to study Pawar’s ability to maintain political dignity while cultivating broad-based support across communities and sectors.

The BJP is increasingly isolated, lacking support from key social and cultural groups. Unlike Sharad Pawar and Uddhav Thackeray, who still draw backing from voices in literature, sports and the arts, the BJP finds few willing to speak for it. Even during the recent Hindi language row, no prominent literary figures defended the party.

Ravindra Chavan has his work cut out. Elections come and go, but unresolved structural issues can linger long after the ballots are counted. His priority must be to revive the party’s morale and rebuild its booth-level machinery, the very backbone of the BJP’s past successes.

One fundamental mistake the party must now avoid is its overreliance on defectors. Offering key positions to outsiders for short-term gain has eroded trust among loyal karyakartas. The BJP is not lacking in talent, but it needs to place faith in its own ranks. As the Marathi saying goes, there’s little wisdom in abandoning your own rooftop to chase someone else’s kite.

Chavan’s elevation comes at a crucial moment. The BJP underperformed in the 2024 general election, particularly in urban centres like Mumbai and the MMR. With civic polls approaching, there is little time to course-correct. A four-time MLA from Kalyan with strong organisational roots, Chavan brings credibility. But he must now unify the second-rung leadership, energise the rank and file, and manage coalition politics with finesse.

Balancing relations with Mahayuti allies - Eknath Shinde’s Shiv Sena and Ajit Pawar’s NCP - without alienating BJP loyalists will be no easy feat. Many within the party already feel marginalised. Chavan must walk a tightrope in staying a dependable ally while reinforcing the BJP’s distinct identity.

The recent Hindi language fiasco further widened the gap between the party and Marathi-speaking voters. Chavan must craft a narrative that embraces regional pride without undermining the party’s national agenda.

He also faces the task of re-engaging with Maharashtra’s intellectuals, artists, and thought leaders. These groups may not swing elections, but they shape public discourse. Token gestures and slogan-heavy campaigns will not do. What is needed is sustained, respectful and genuine outreach.

Finally, Chavan must restore internal discipline. Conflicting messages and unclear alliance dynamics have sown confusion. His challenge is to bring coherence, unity, and confidence back to a party struggling to find its voice in Maharashtra in the road leading to the 2029 Assembly and Parliamentary polls. Ravindra Chavan’s leadership could well mark a turning point for the BJP in Maharashtra. The state’s politics are layered and unpredictable, but with quiet resolve, cultural nuance and disciplined grassroots work, the party can recover lost ground.

To do so, Chavan must first look inward. Rebuilding the party’s internal machinery matters more than photo-ops with rivals in five-star hotels or private residences. If dialogue with opposition leaders is necessary, it should take place on the BJP’s turf.

A final word of caution: the media will always chase spectacle. Chavan must resist the lure of headlines. What the BJP – and Maharashtra - needs most urgently is substance over showmanship.

Comments